Chaya Ocampo Go

22 September 2016

The most urgent work of protecting and securing water falls on those whose rights and responsibilities to it are most threatened. The most vulnerable are hardly gated communities or commercial complexes in the Philippines, nor are they likely to be white upper and middle-class neighbourhoods in North America whose comforts are ensured plentiful reserves (see Gosine and Teelucksingh 2008).

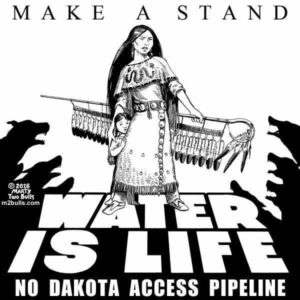

This article makes the transnational connections between the momentous Standing Rock resistance against the #North Dakota Pipeline and drought-stricken farming and Indigenous communities in the Philippines—both of whose ongoing struggles to survive today are at the brunt of the climate crisis.

Water Protectors in #North Dakota

At the time of this writing, the #Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is leading a historic movement all across Turtle Island* in opposition to the #Dakota Access Pipeline. Longtime Native American activist, #Winona LaDuke, offers a powerful analysis of how the fossil fuel industry continues to dispossess Indigenous peoples from their territories in the Global North while wrecking havoc on communities in the Global South. In an interview with Amy Goodman of Democracy Now!, she strings for us a transnational web of multiple oppressions created by extractivism: from the colonial and ongoing dispossession of sovereign tribes from their lands, intergenerational trauma, gendered abuse and violence against Aboriginal women, to State neglect and economic policies prioritizing ‘profits over people’.

It is critical to name how racism, colonialism, sexism, and extractivism collude and create these imploding crises. In the context of the U.S., Benjamin Chavis coined the term ‘#environmental racism’ to expose “the intentional siting of hazardous waste sites, landfills, incinerators and polluting industries in areas inhabited mainly by Blacks, Latinos, Indigenous peoples, Asians, migrant farm workers and low-income peoples in the United States” (Gosine and Teelucksingh 2008, 4).

It is critical to name how racism, colonialism, sexism, and extractivism collude and create these imploding crises. In the context of the U.S., Benjamin Chavis coined the term ‘#environmental racism’ to expose “the intentional siting of hazardous waste sites, landfills, incinerators and polluting industries in areas inhabited mainly by Blacks, Latinos, Indigenous peoples, Asians, migrant farm workers and low-income peoples in the United States” (Gosine and Teelucksingh 2008, 4).

The North Dakota pipeline will run through the Missouri River, which leads into the Mississippi River Water Basin, affecting the supply of drinking water for over 18 million people. Not only has there been a lack of free and prior informed consent to construct the pipelines, but there is also no regulatory body directly responsible for any environmental destruction caused by accidents.

LaDuke insists that their actions to protect the Missouri River running through Lakota/Dakota/Nakoda treaty lands also matters to China, India, Venezuela, and the rest of the world who may be watching. If I could speak to her I would say as a Filipina, “Yes, and it matters to the Philippines too. The pipelines you refuse to poison your waters are the very same forces drying up the lands of our #Lumads and farmers.”

Farmers and Scorched Waterways in the Philippines

The gunning down of drought-affected Lumads and farmers at #Kidapawan City, Philippines who were demonstrating for rice rations on April 1st 2016 is not “just” about #climate change.

The El Niño spell is political: the inability of impacted communities to cope with drought that had already been reported by the Philippine weather bureau PAGASA in 2015 is social injustice; the shooting ordered by the North #Cotabato governor and the corrupted disbursal of calamity funds is criminal State neglect of the poor and Indigenous; and as the Paris Climate Agreement already attests to, the freak weather conditions combatting the Philippines is a product of the industrialized bloc’s carbon emissions. The most vulnerable suffer from violent changes in the climate they are least responsible for.

The CDRC Regional Centres directly affected by the recent El Niño are the #Cagayan Valley Disaster Response Centre (CVDRC) and the #Disaster Response Centre (DIRECT). They reported that their areas have been suffering from minimal rainfall since October 2015. The dry spell was forecasted to affect over 32 provinces up until June 2016. The shooting of the demonstrators at Kidapawan was only the climactic turn of a long string of tragedies.

To date, CDRC has been able to serve 1,397 families in #South Cotabato, Cotabato, #Sultan Kudarat and #Sarangani (SOCCSKSARGEN) and is in its fourth and final delivery of relief; CDRC has also served 100 families in Cagayan in a one-time relief delivery. Its Regional Centres continue to work alongside their affected partner communities as they have done in the last decades to address root causes of vulnerability.

Although the El Niño period has officially ended and small amounts of rain have returned, the effects of the drought are expected to last longer. Worm infestation in corn fields and rat infestation in rice fields occurred resulting to harvest failure. Small landslides due to loose soil as a result of desertification also threaten certain areas of production. Sustained livelihood assistance in the form of seeds, livestock and irrigation remains critically needed. To think of El Niño as a singular event, already past and done, ignores the long-lasting social and economic impacts it has in the affected communities.

Intensifying storms and droughts experienced in the Philippines are directly linked to the extraction and consumption of #fossil fuels in the Global North—not excluding the tar sands in Canada and the continuing construction of pipelines, which is steadfastly resisted by Standing Rock and over 180 other tribal nations. Naomi Klein’s film “This Changes Everything” (see Klein 2014) argues precisely for making these transnational connections as she followed many communities across the globe who are at the frontlines.

Apart from its compelling optimism for grassroots climate justice movements, in my opinion, the film begs for a longer and deeper look at the grievous and everyday violences all too rife, yet still largely invisible, in the Global South: from the unspeakable catastrophe wrought by Super Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda in the Philippines, or of drought-stricken farmers gunned down in Mindanao, climate change has only magnified the gravity of many pre-existing and pressing socio-political issues in these communities.

Water is a Human Right-Responsibility

There is a resounding urgency in the call for a just transition out of fossil fuels and towards #renewable energies, especially for the most vulnerable communities in the Philippines—what LaDuke calls “energy independence” for the many tribes standing at the Sacred Stone Camp today.

Historian and activist, Rebecca Solnit, asks of the Standing Rock protest: “Is this a new #civil rights movement where environmental and human rights meet?” Perhaps, although these struggles are certainly not-so-new. Imagine Lumads with their ancestral domains secured and rivers protected from industrial contamination and without further threats of militarization and displacement. Imagine Filipina/o farmers with their land tenure and water flows safe for their own safe drinking, irrigation, and food security. Imagine First Nations** in full governance over the health of their traditional lands, waters, and their lives.

The most urgent work of protecting the waters fall on those whose rights and responsibilities to it are most threatened. Indigenous peoples, farming and fishing communities whose lives depend directly on the land and waters: their survival determines the futures our world can live in.

#WaterIsLife BigasHindiBala

—

*The precolonial name of North America

** Indigenous peoples in Canada

The author is a Filipina scholar at York University and a Research Fellow for the Citizens’ Disaster Response Centre. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of CDRC.

Resources

Gosine, A., and C. Teelucksingh. 2008. Environmental Justice and Racism in Canada: An Introduction. Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Limited.

Klein, N. 2014. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. USA: Simon & Schuster.

Leave a Reply